It is a lively Autumn morning. At two minutes to nine, a crowded city bus pulls into the bus stop near Saint Elisabeth Convent. It is the middle of the rush hour. All are hurrying to work. But some among the crowd is particularly eager. They are rushing ahead of the rest towards the Convent. “Careful, Tatyana! Do not break the heels of your shoes,” jokes a brother, also on the run. Another sister is anxious: “Where is my headcover? Did I leave it at home? Take it out, quick!” Many are being late for work, but only the iconographers are running to be on time. They have a disciplined and demanding supervisor, Father Sergius, who is always upset when his people are late. The working day at the workshop starts at nine when everyone reads the canon to Venerable Father Saint Andrey Rublev. As they welcome visitors and show them around the workshop, the sisters will always say: “An iconographer’s day starts with a prayer”. They are right. The door of the workshop opens and closes every now and then as the late iconographers are coming to the measured reading of the irmoses and singing of the troparions.

The icon-painting workshop is its people. They are a very diverse lot; they even look different. Some resemble photo models, others appear more like pilgrims. Some might be called bonnie lasses, others look like middle-aged women with shopping bags. Some of the icon-painters are monastics. All are working together. What do they have in common? God brought them all together, in some unique and special way.

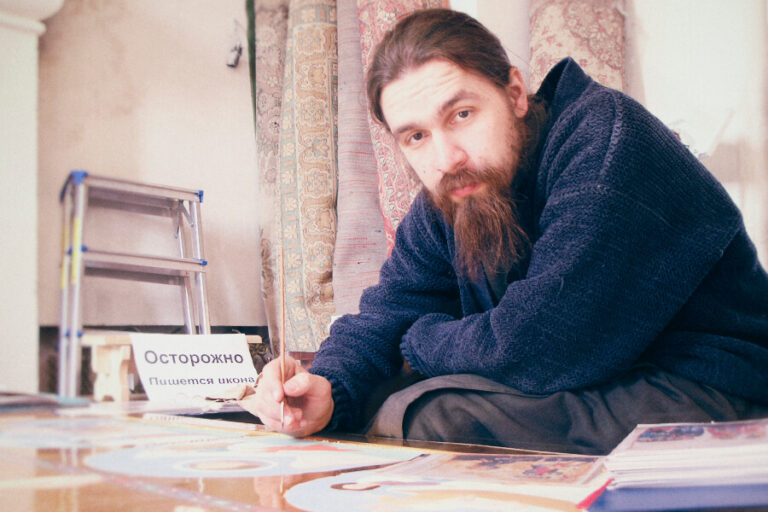

Priest Sergius Nezhbort, leader of the icon-painting workshop, at work

In the beginning, there were only a handful of people. The Convent was still not there, and the building of its first church had not even begun. The first few were the parishioners of the Cathedral of Saint Peter and Paul, the students of painting at the academy of arts. They came to church at almost the same time and took iconography classes from Father Igor Latushko from the cathedral. When the lay sisterhood was established, they became its members. At some point, we had an idea: why not paint the icons together. Good ideas will materialise in most cases. This one was not an exception, and soon a suitable location for the studio was found. It was the basement of the mental health hospital.

When a church began to be built next to the hospital, they asked us almost immediately to begin work on the iconostasis. The hospital’s chief doctor let us use a room on hospital grounds for painting the icons. Large boards for the icons were commissioned in the winter of 1998. Father Sergius remembers the long hours spent in the hospital basement grounding the boards. Still a student at the Academy of Arts, he was coming to the studio to ground the icon boards with thin layers of paint, up to 10 – 15 layers per board. It was spring. Everything was in blossom. Father Sergius recalls:

“It was late in the evening, and I was alone. I would put a layer of the grounding paint, which takes about thirty minutes to dry, and I dozed off while I was waiting. I set the alarm to wake up every forty minutes to apply a new layer. In those years, I used to pour hot tea over myself quite a lot. I would make myself some tea but would fall asleep before I could take the first sip. Spilling the tea over me would wake me up. Sometimes, I would wake up from falling off the chair. I one fell over with a cup of tea in my hand. Ah, those were my happy days…”

The icon-painting workshop was launched at the Convent during the bright week of Easter, in 1999. Initially, all its workforce were two monastic sisters, who grounded the boards, learned to do the gold background and apply drying oil. Today, the assistants are doing all this work, while the painters focus only on painting. Everyone could bear with this arrangement, despite the initial difficulty. I also remember visiting a full-scale icon painting workshop at the Cathedral of Saint Peter and Paul. We entered it with great awe. Someone who enters the altar area for the first time might have felt the same way. We asked the icon painters to let us help him in any way we could, so we could come again. They accepted our offer, so we returned to help with washing the paint jars and the floors. We felt deeply honoured to be doing this because we could be present at the birth of the icons. Eventually, we learned the correct techniques to apply the grounding and mix the mineral-based paints. It is a great miracle indeed that the Byzantine icon-painting techniques have survived, and icons are still being painted in the same way as the great masters like Andrey Rublev used to paint them from the 12th to the 15th centuries. Modern painters no longer use them. One of the books on icon painting we never used to part with was “The Work of an Icon Painter” by Nun Juliania (Sokolova); we were taking great care to remember all the details and secrets of the trade. I also recall our visits to the Tretyakov Gallery of Moscow to view examples of the old icon painting techniques. They inspired us a lot. One could barely find such examples anywhere in Belarus. We also worked hard to put together a collection of books, reprints and photos of the old icons, mosaics and frescos. This task has become a lot easier now with the advent of computers. Newcomers to the workshops no longer have to go up a very steep learning curve, as most processes are already well-established. Before the computers, we used to toil away like the youth from Tarkovsky’s film “Andrey Rublev” as he was casting his bell. But our growth as a workshop was a happy and exciting time for us.

Matushka Larisa and Father Sergius Nezhbort in ‘those happy days’

As we grew, new brothers and sisters joined our ranks, whom we nevertheless knew quite well. The workshop was our life, as were the sisterhood, the liturgies, the gatherings, and the talks of our spiritual father. No-one could imagine themselves without the workshop. In truth, it became like home to many. While still in the hospital basement, we put behind the wardrobe a king-sized bed. It was large enough for three sisters to sleep in. The sleeping places for the brothers were on the other side of the wardrobe. We would spend our nights there before the early morning services. While the church was still being built, there were only three liturgies each week, one on Thursdays, at the hospital’s rehabilitation centre, one on Fridays at the chapel at the care home, and one on Sundays at the church under construction. When the dormitory building was complete, the workshop moved there from the hospital basement. All the sisters who joined us, in the beginning, have either married or joined the Convent. In turn, the brothers – icon painters and not – have established a group called “Mount Athos Cabin in Honour of the Holy Theotokos”, which was based at the workshop and gathered outside of its working hours.

Already, the worship services at the Convent had begun to be held daily, starting from four in the morning. Most of the brothers were assisting the priests as sextons and attending the night offices regularly. The gathering of the ‘cabin group’ began with a late evening meal, usually consisting of instant pasta, ketchup and tinned fish and accompanied by a long and lively spiritual debate. When finished, everyone read the prayer rule, and afterwards the Akathist to the Holy Theotokos. The brothers are still reading the Akathist after the evening service every Friday. In those times, we read it in candlelight, and we burned incense. The brothers took turns to burn the incense. They were using a toy-sized incensory with real rattles and incense oil. One of the brothers eventually became a deacon, and now uses an adult-sized incensory. The sisters were not trusted to burn the incense. In the Mount Athos cabin society, there were not supposed to be any sisters. We nevertheless had a few, and they went by the names Father Irynarkh and Father Laurentius, to keep to the rules of Mount Athos.

Father Andrey was our frequent guest, and each visit from him was a special event. We also had our bedtime rituals. We put up the makeshift beds, which occupied all of the workshop’s free space. Four chairs (still from the hospital basement) were put in a row to serve as beds for the brothers. One brother who joined us periodically brought with him a large folding bed with an unusually thick mattress. He was great fun to watch as he was unfolding it and putting it up. Another brother was a practitioner of hesichasm and secluded living, and he would always sleep on a sleeping bag on the floor. He rolled out his khaki-coloured bed and made multiple bows. Some say that when he was occupying a room on the third floor, the sound of him bowing was so loud that the occupants underneath could not go to sleep until he finished. But our fathers and brothers had no difficulty sleeping. Sometimes, Valery, a sexton, came to join us, convinced by our brothers who could not bear to see him trying to go to sleep in an old armchair in the kitchen despite the pain in his legs. He was serious and mature, and he always stayed away from the noisy gatherings of the younger brothers. Now, he is a priest, solid and well-respected. What was going to become of all the rest?

One of the brothers was saying, time and again: “We are living our happiest moments. Eventually, we are going to go our separate ways. We will grow up, and become solid and barely approachable.” None of us believed him. But sadly, we change. Some brothers and sisters have married, others have joined the monastery. The cabin society fell apart. The brother was right! Yet we have remained connected spiritually. “The most important thing is to find God, we will all be one in the Kingdom of Heaven, and our unity will be even stronger,” we all thought.

But the workshop lives on. After many years, it has changed and grown, and become more formal and fundamental in some ways. Some people have left us, some for family reasons, others to do different obedience at the Convent. New people are coming. They are taking time to adjust, but when they do, they become our close family. We celebrate the coming of each new person as a miracle of God and an act of His Divine providence. For all the people here, icon painting is life, and God is the end.

As Father Igor has said, some are icon-painters from the capital letter; they create masterpieces. Others find salvation around the icons. The latter is true for most of us.

Priest Sergius and Matushka Larisa Nezhbort with the newly painted icons

It often feels as if we are denying ourselves something quite essential, and are giving it up to God. In truth, it is a great privilege to be at His service by giving Him our talent, time and effort, our hearts and our minds. The chance to do so is something to be grateful for, and never to be missed.

… The evening has come. It is already dark at half-past seven. Tatyana, an icon painter, is looking for a large bag.

“What do you need it for?” I asked.

“To take the unfinished icon home.”

“Are you sure? Would not you like to rest?”

“I have nothing else to do tonight anyway. So I will have some tea and paint until midnight or so.”

Our life is going on.

We will gladly accept orders for wedding, family, baptismal, named, church and other types of icons.

By Matushka Larisa Nezhbort

The workshop now: